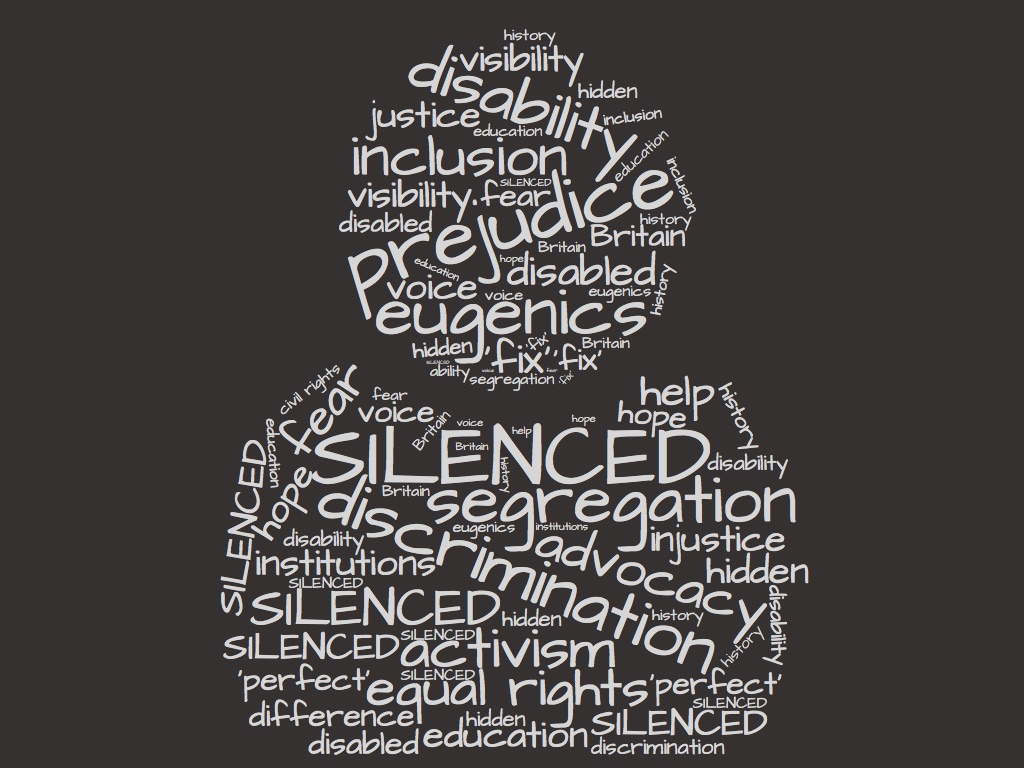

Silenced

…inclusion is something everyone wants in their hearts…

(Micheline Mason)

As part of my role as Inclusion & Visibility Subcommittee Co-convenor in my professional association (British Association of Dramatherapists), I host events which invite dramatherapists to explore themed material highlighting marginalised communities and share their thoughts at both a professional and personal level.

The BBC documentary, ‘Silenced: The Hidden Story of Disabled Britain’, was the subject of one of these events, which powerfully revealed that we all have something to learn when it comes to the history and lived experiences of the disabled community. There is unconscious bias and prejudice in all of us and, particularly for therapists, we have to be open to hear this… are we?

‘Prejudice towards disability is very rarely spoken of…’ and ‘Disability is largely feared…’. With attitudes towards people with disabilities involving, ‘…it would have been better if you were able-bodied, or it would have been better if you weren’t here at all…’; this documentary questioned whether society could ‘…ever overcome centuries of injustice and fear…’ towards the disabled community (Cerrie Burnell).

The documentary tracked the history of disabled people being marginalised in Britain, where they were locked up in institutions and exiled from life because there was something different about their body or mind during the Victorian era. Disabled and poverty-stricken people were frequently hidden from society in workhouses.

Mary Dendy (a social reformer, benefactor and eugenicist), founded Sandlebridge Colony, an institution that was ‘…a home for the permanent care of the feeble-minded.’ (Cerrie Burnell) Impoverished children and young people who were born with disfigurements, deaf, blind, or (as one commentator stated) because they were perceived to be ‘very stupid’, found themselves imprisoned in such places. Their voices were silenced and their lives were disregarded as they were shut away from the rest of humanity.

‘Feeble-minded’ was an umbrella term that was widely used to describe individuals of various disabilities and difficulties. A brief look at the 1861 Parliamentary Report revealed how people with disabilities were listed using appalling and discriminative language by today’s standards. However, it was an insight and a reflection of how this was acceptable and commonplace, as well as how disability was perceived back then.

Heartbreaking stories of how individuals were robbed of their freedom under the 1913 Mental Deficiency Act were also shared. One such case was the story of Jean Gambell who spent over 70 years institutionalised. Gambell’s younger brothers were uncertain as to why she was admitted, and there was speculation that Gambell was sectioned after contracting Meningitis as a teenager. Repeated appeals to be released, made by her father, were all rejected. Gambell’s brothers only had vague recollections of her and had presumed she was dead: it was ‘…as though she never existed.’ They were unaware that she had been ‘…put away in a mental institution…’, and only discovered that their sister was still alive by chance. Gambell died shortly after being reunited with her brothers.

The documentary captured a dark past where disabled people were viewed as ‘…disabled in every way. You were mentally disabled, physically disabled, morally disabled…’ (Micheline Mason). With this in mind, Britain actively engaged in eugenics until World War II.

This was later replaced with a medical model of disability that focused on ‘fixing’ nonconformist bodies to make them ‘perfect’. Ann Macfarlane shared her experiences of how Still’s Disease was treated: having her bones purposefully (and repeatedly) broken and reset in plaster as a child. This led to having most of her body encased in plaster, like a suit of immovable armour.

In contrast to this medical model to ‘perfect’ disabled individuals, Dr. Ludwig Gutman (a Jewish physician who escaped Nazi persecution) held a different view. His pioneering work of seeing the disabled community as capable members of society, and using sport to aid this process, led to the first Paralympic Games.

The documentary continued to mark several movements within the disabled community, where the work of activists, such as Paul Hunt and John Evans, promoted the materialisation of the social model of disability which sought to reframe disability as a civil rights issue. Voices that had been silenced were insistent that they would be heard, and that the disabled community were entitled to equal rights.

Interviews with Baroness Jane Campbell and Alia Hassan documented the continued fight for civil rights. Protests from the disabled community ensued, where London traffic was brought to a standstill as they challenged a transport system that only made provision for able-bodied people. Charity events were called into question as activists chanted ‘rights not charity’, voicing the need for inclusion rather than segregation – such as access to paid employment. These protests paved the way for the 1995 Disability Discrimination Act, which witnessed some protection and rights for the disabled community: for example, employment and travel. However, it was not until the 2010 Equality Act that disabled people were offered equal rights as well as protection from direct discrimination in areas beyond the realms of employment.

Although a triumph for the disabled community, the documentary highlighted the fragility of these rights as benefits and services were (and continue to be) dramatically cut by the Government during the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. The documentary called for vigilance ‘…to make sure that those rights suddenly aren’t taken away in the middle of the night when no one is looking.’ (Cerrie Burnell)

The documentary noted the lasting impacts of segregation, where disabled children who were capable of attending mainstream schools were denied this right and privilege. Micheline Mason, diagnosed with Brittle Bones Disease, was one such child. She campaigned for integrated schools so that disabled children (including her daughter), did not face the same seclusion that she did. Mason drew attention to the inclusive nature of children and the fact that able-bodied children wanted ‘…our friends in school with us, we had a lot of fun together…’. It was this sentiment that affected the most change.

This documentary shared present day experiences where Cerrie Burnell, who was born without the lower part of her right arm, was the subject of publicised angry letters from parents complaining that her appearance would frighten their children when working on CBeebies. She reflected how in today’s society, disability is not viewed as ‘…sexy or powerful…’, but rather as ‘vulnerable’ and ‘incapable’.

Society views take time to change, and there appears to be a ‘shadow’ from the trauma of the 19th century institutions that contributes to the 21st century views and treatment of disabled people: ‘…the attitudes of the past still shape the lives of people today.’ (Cerrie Burnell) Benefits in support of the disabled community are cut, discrimination is still present, and there is still pressure for disabled people to conform to the aesthetically pleasing ‘perfect’ body. For example, encouraged to use prosthetics as a means of fitting in and not being socially rejected.

The ending statement summarises the history, leaving viewers with the notion that there is still more work to be done for the equality, inclusion, visibility and wellness of the disabled community:

It was prejudice that segregated us into institutions. It was a fear of difference that made doctors try to fix us and it was discrimination that shut us out, and after 100 years we’re still not there yet.

(Carrie Burnell)

The documentary, ‘Silenced: The Hidden Story of Disabled Britain’, is available to watch on BBC iPlayer.

June 2021, Hayley Southern